Hall effect

The Hall effect is the production of a voltage difference (the Hall voltage) across an electrical conductor, transverse to an electric current in the conductor and a magnetic field perpendicular to the current. It was discovered by Edwin Hall in 1879.[1]

The Hall coefficient is defined as the ratio of the induced electric field to the product of the current density and the applied magnetic field. It is a characteristic of the material from which the conductor is made, since its value depends on the type, number, and properties of the charge carriers that constitute the current.

Discovery

The Hall effect was discovered in 1879 by Edwin Herbert Hall while he was working on his doctoral degree at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. His measurements of the tiny effect produced in the apparatus he used was an experimental tour de force, accomplished 18 years before the electron was discovered.

Theory

The Hall effect comes about due to the nature of the current in a conductor. Current consists of the movement of many small charge carriers, typically electrons, holes, ions (see Electromigration) or all three. When a magnetic field is present that is perpendicular to the direction of motion of moving charges, these charges experience a force, called the Lorentz force.[2] When such a magnetic field is absent, the charges follow approximately straight, 'line of sight' paths between collisions with impurities, phonons, etc. However, when a perpendicular magnetic field is applied, their paths between collisions are curved so that moving charges accumulate on one face of the material. This leaves equal and opposite charges exposed on the other face, where there is a scarcity of mobile charges. The result is an asymmetric distribution of charge density across the Hall element that is perpendicular to both the 'line of sight' path and the applied magnetic field. The separation of charge establishes an electric field that opposes the migration of further charge, so a steady electrical potential builds up for as long as the charge is flowing.

It should be noted that in the classical view, there are only electrons moving in the same average direction both in the case of electron or hole conductivity. This cannot explain the opposite sign of the Hall effect observed. The difference is that electrons in the upper bound of the valence band have opposite group velocity and wave vector direction when moving, which can be effectively treated as if positively charged particles (holes) moved in the opposite direction to that of the electrons.

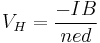

For a simple metal where there is only one type of charge carrier (electrons) the Hall voltage VH is given by

where I is the current across the plate length, B is the magnetic field, d is the depth (thickness) of the plate, e is the electron charge, and n is the charge carrier density of the carrier electrons.

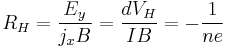

The Hall coefficient is defined as

where j is the current density of the carrier electrons, and  is the induced electric field. In SI units, this becomes

is the induced electric field. In SI units, this becomes

As a result, the Hall effect is very useful as a means to measure either the carrier density or the magnetic field.

One very important feature of the Hall effect is that it differentiates between positive charges moving in one direction and negative charges moving in the opposite. The Hall effect offered the first real proof that electric currents in metals are carried by moving electrons, not by protons. The Hall effect also showed that in some substances (especially p-type semiconductors), it is more appropriate to think of the current as positive "holes" moving rather than negative electrons. A common source of confusion with the Hall Effect is that holes moving to the left are really electrons moving to the right, so one expects the same sign of the Hall coefficient for both electrons and holes. This confusion, however, can only be resolved by modern quantum mechanical theory of transport in solids.[3]

It must be noted though that the sample inhomogeneity might result in spurious sign of the Hall effect, even in ideal van der Pauw configuration of electrodes. For example, positive Hall effect was observed in evidently n-type semiconductors.[4]

Hall effect in semiconductors

When a current-carrying semiconductor is kept in a magnetic field, the charge carriers of the semiconductor experience a force in a direction perpendicular to both the magnetic field and the current. At equilibrium, a voltage appears at the semiconductor edges.

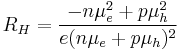

The simple formula for the Hall coefficient given above becomes more complex in semiconductors where the carriers are generally both electrons and holes which may be present in different concentrations and have different mobilities. For moderate magnetic fields the Hall coefficient is[5]

where  is the electron concentration,

is the electron concentration,  the hole concentration,

the hole concentration,  the electron mobility,

the electron mobility,  the hole mobility and

the hole mobility and  the absolute value of the electronic charge.

the absolute value of the electronic charge.

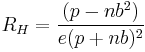

For large applied fields the simpler expression analogous to that for a single carrier type holds.

with

Quantum Hall effect

For a two dimensional electron system which can be produced in a MOSFET. In the presence of large magnetic field strength and low temperature, one can observe the quantum Hall effect, which is the quantization of the Hall voltage.

Spin Hall effect

The spin Hall effect consists in the spin accumulation on the lateral boundaries of a current-carrying sample. No magnetic field is needed. It was predicted by M.I. Dyakonov and V.I. Perel in 1971 and observed experimentally more than 30 years later, both in semiconductors and in metals, at cryogenic as well as at room temperatures.

Quantum spin Hall effect

For HgTe two dimensional quantum wells with strong spin-orbit coupling, in zero magnetic field, at low temperature, the Quantum Spin Hall effect has been recently observed.

Anomalous Hall effect

In ferromagnetic materials (and paramagnetic materials in a magnetic field), the Hall resistivity includes an additional contribution, known as the anomalous Hall effect (or the extraordinary Hall effect), which depends directly on the magnetization of the material, and is often much larger than the ordinary Hall effect. (Note that this effect is not due to the contribution of the magnetization to the total magnetic field.) Although a well-recognized phenomenon, there is still debate about its origins in the various materials. The anomalous Hall effect can be either an extrinsic (disorder-related) effect due to spin-dependent scattering of the charge carriers, or an intrinsic effect which can be described in terms of the Berry phase effect in the crystal momentum space (k-space).[6]

Hall effect in ionized gases

(See electrochemical instability)

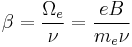

The Hall effect in an ionized gas (plasma) is significantly different from the Hall effect in solids (where the Hall parameter is always very inferior to unity). In a plasma, the Hall parameter can take any value. The Hall parameter, β, in a plasma is the ratio between the electron gyrofrequency, Ωe, and the electron-heavy particle collision frequency, ν:

where

- e is the elementary charge (approx. 1.6 × 10-19 C)

- B is the magnetic field (in teslas)

- me is the electron mass (approx. 9.1×10-31 kg).

The Hall parameter value increases with the magnetic field strength.

Physically, the trajectories of electrons are curved by the Lorentz force. Nevertheless when the Hall parameter is low, their motion between two encounters with heavy particles (neutral or ion) is almost linear. But if the Hall parameter is high, the electron movements are highly curved. The current density vector, J, is no longer colinear with the electric field vector, E. The two vectors J and E make the Hall angle, θ, which also gives the Hall parameter:

Applications

Hall probes are often used as magnetometers, i.e. to measure magnetic fields, or inspect materials (such as tubing or pipelines) using the principles of magnetic flux leakage.

Hall effect devices produce a very low signal level and thus require amplification. While suitable for laboratory instruments, the vacuum tube amplifiers available in the first half of the 20th century were too expensive, power consuming, and unreliable for everyday applications. It was only with the development of the low cost integrated circuit that the Hall effect sensor became suitable for mass application. Many devices now sold as Hall effect sensors in fact contain both the sensor as described above plus a high gain integrated circuit (IC) amplifier in a single package. Recent advances have further added into one package an analog-to-digital converter and I²C (Inter-integrated circuit communication protocol) IC for direct connection to a microcontroller's I/O port.

Advantages over other methods

Hall effect devices when appropriately packaged are immune to dust, dirt, mud, and water. These characteristics make Hall effect devices better for position sensing than alternative means such as optical and electromechanical sensing.

When electrons flow through a conductor, a magnetic field is produced. Thus, it is possible to create a non-contacting current sensor. The device has three terminals. A sensor voltage is applied across two terminals and the third provides a voltage proportional to the current being sensed. This has several advantages; no additional resistance (a shunt, required for the most common current sensing method) need be inserted in the primary circuit. Also, the voltage present on the line to be sensed is not transmitted to the sensor, which enhances the safety of measuring equipment.

Disadvantages compared with other methods

Magnetic flux from the surroundings (such as other wires) may diminish or enhance the field the Hall probe intends to detect, rendering the results inaccurate. Also, as Hall voltage is often on the order of millivolts, the output from this type of sensor cannot be used to directly drive actuators but instead must be amplified by a transistor-based circuit.

Contemporary applications

Hall effect sensors are readily available from a number of different manufacturers, and may be used in various sensors such as rotating speed sensors (bicycle wheels, gear-teeth, automotive speedometers, electronic ignition systems), fluid flow sensors, current sensors, and pressure sensors. Common applications are often found where a robust and contactless switch or potentiometer is required. These include: electric airsoft guns, triggers of electropneumatic paintball guns, go-cart speed controls, smart phones, and some global positioning systems.

Ferrite toroid Hall effect current transducer

Hall sensors can detect stray magnetic fields easily, including that of Earth, so they work well as electronic compasses: but this also means that such stray fields can hinder accurate measurements of small magnetic fields. To solve this problem, Hall sensors are often integrated with magnetic shielding of some kind. For example, a Hall sensor integrated into a ferrite ring (as shown) can reduce the detection of stray fields by a factor of 100 or better (as the external magnetic fields cancel across the ring, giving no residual magnetic flux). This configuration also provides an improvement in signal-to-noise ratio and drift effects of over 20 times that of a bare Hall device. The range of a given feedthrough sensor may be extended upward and downward by appropriate wiring. To extend the range to lower currents, multiple turns of the current-carrying wire may be made through the opening. To extend the range to higher currents, a current divider may be used. The divider splits the current across two wires of differing widths and the thinner wire, carrying a smaller proportion of the total current, passes through the sensor.

The principle of increasing the number of windings a conductor takes around the ferrite core is well understood, each turn having the effect of multiplying the current under measurement. Often these additional turns are carried out by a staple on the PCB.

Split ring clamp-on sensor

A variation on the ring sensor uses a split sensor which is clamped onto the line enabling the device to be used in temporary test equipment. If used in a permanent installation, a split sensor allows the electric current to be tested without dismantling the existing circuit.

Analog multiplication

The output is proportional to both the applied magnetic field and the applied sensor voltage. If the magnetic field is applied by a solenoid, the sensor output is proportional to the product of the current through the solenoid and the sensor voltage. As most applications requiring computation are now performed by small (even tiny) digital computers, the remaining useful application is in power sensing, which combines current sensing with voltage sensing in a single Hall effect device.

Current sensing

By sensing the current provided to a load and using the device's applied voltage as a sensor voltage it is possible to determine the power dissipated by a device.

Position and motion sensing

Hall effect devices used in motion sensing and motion limit switches can offer enhanced reliability in extreme environments. As there are no moving parts involved within the sensor or magnet, typical life expectancy is improved compared to traditional electromechanical switches. Additionally, the sensor and magnet may be encapsulated in an appropriate protective material. This application is used in brushless DC motors.

Automotive ignition and fuel injection

Commonly used in distributors for ignition timing (and in some types of crank and camshaft position sensors for injection pulse timing, speed sensing, etc.) the Hall effect sensor is used as a direct replacement for the mechanical breaker points used in earlier automotive applications. Its use as an ignition timing device in various distributor types is as follows. A stationary permanent magnet and semiconductor Hall effect chip are mounted next to each other separated by an air gap, forming the Hall effect sensor. A metal rotor consisting of windows and tabs is mounted to a shaft and arranged so that during shaft rotation, the windows and tabs pass through the air gap between the permanent magnet and semiconductor Hall chip. This effectively shields and exposes the Hall chip to the permanent magnet's field respective to whether a tab or window is passing though the Hall sensor. For ignition timing purposes, the metal rotor will have a number of equal-sized tabs and windows matching the number of engine cylinders. This produces a uniform square wave output since the on/off (shielding and exposure) time is equal. This signal is used by the engine computer or ECU to control ignition timing. Many automotive Hall effect sensors have a built-in internal NPN transistor with an open collector and grounded emitter, meaning that rather than a voltage being produced at the Hall sensor signal output wire, the transistor is turned on providing a circuit to ground through the signal output wire.

Wheel rotation sensing

The sensing of wheel rotation is especially useful in anti-lock brake systems. The principles of such systems have been extended and refined to offer more than anti-skid functions, now providing extended vehicle handling enhancements.

Electric motor control

Some types of brushless DC electric motors use Hall effect sensors to detect the position of the rotor and feed that information to the motor controller. This allows for more precise motor control

Industrial applications

Applications for Hall Effect sensing have also expanded to industrial applications, which now use Hall Effect joysticks to control hydraulic valves, replacing the traditional mechanical levers with contactless sensing. Such applications include; Mining Trucks, Backhoe Loaders, Cranes, Diggers, Scissor Lifts, etc.

Spacecraft propulsion

A Hall effect thruster (HET) is a relatively low power device that is used to propel some spacecraft, once they get into orbit or farther out into space. In the HET, atoms are ionized and accelerated by an electric field. A radial magnetic field established by magnets on the thruster is used to trap electrons which then orbit and create an electric field due to the Hall effect. A large potential is established between the end of the thruster where neutral propellant is fed and the part where electrons are produced, so electrons trapped in the magnetic field cannot fall down the potential, and thus are extremely energetic allowing them to ionize neutral atoms. Neutral propellant is pumped into the chamber and is ionized by the trapped electrons. Then positive ions and electrons are ejected from the thruster as a quasineutral plasma, creating thrust.

The Corbino effect

The Corbino effect is a phenomenon involving the Hall effect, but a disc-shaped metal sample is used in place of a rectangular one. Because of its shape the Corbino disc allows the observation of Hall-effect–based magnetoresistance without the associated Hall voltage.

A radial current through a circular disc, subjected to a magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of the disc, produces a "circular" current through the disc.[7]

The absence of the free transverse boundaries renders the interpretation of the Corbino effect simpler than that of the Hall effect.

See also

References

- ^ Edwin Hall (1879). "On a New Action of the Magnet on Electric Currents". American Journal of Mathematics (American Journal of Mathematics, Vol. 2, No. 3) 2 (3): 287–92. doi:10.2307/2369245. JSTOR 2369245. http://www.stenomuseet.dk/skoletj/elmag/kilde9.html. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ^ "The Hall Effect". NIST. http://www.eeel.nist.gov/812/effe.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ^ N.W. Ashcroft and N.D. Mermin "Solid State Physics" ISBN 978-0030839931

- ^ T. Ohgaki et al. "Positive Hall coefficients obtained from contact misplacement on evident n-type ZnO films and crystals" J. Mat. Res. 23(9) (2008) 2293

- ^ Kasap, Safa. "Hall Effect in Semiconductors". Archived from the original on 2008-11-01. http://www.webcitation.org/5c0UeBBsZ.

- ^ N. A. Sinitsyn (2008). "Semiclassical Theories of the Anomalous Hall Effect". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 20 (2): 023201. arXiv:0712.0183. Bibcode 2008JPCM...20b3201S. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/20/02/023201.

- ^ Adams, E. P. (1915). "The Hall and Corbino effects". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (American Philosophical Society) 54 (216): 47–51. ISBN 9781422372562. http://books.google.com/?id=OFYLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA47. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

Further reading

- Classical Hall effect in scanning gate experiments: A. Baumgartner et al., Phys. Rev. B 74, 165426 (2006), doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.74.165426

External links

- Patents

- U.S. Patent 1,778,796, P. H. Craig, System and apparatus employing the Hall effect

- General

- Interactive Java tutorial on the Hall Effect National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- Science World (wolfram.com) article.

- "The Hall Effect". nist.gov.

- Hall, Edwin, "On a New Action of the Magnet on Electric Currents". American Journal of Mathematics vol 2 1879.

- Spin Hall Effect Detected at Room Temperature

- Hall Effect Sensing and Application. Honeywell documentation on hall effect sensing, interfacing and applications.

- Table with Hall coefficients of different elements at room temparature.